© MMXXIV T A Bird Classics

Classics resources

I want to argue that the use of running

vocabularies is extremely helpful for those

attempting to learn the ancient languages.

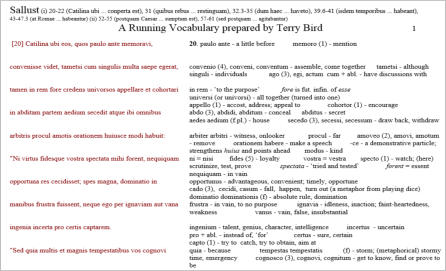

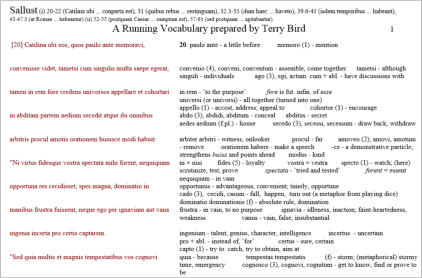

For those unfamiliar with such aids, please

look at my sample pages.

I began giving out running vocabularies for

Latin and Greek texts over thirty five years

ago at Colchester Royal Grammar School. I was sometimes aware

that others were trying this out (for instance, Reading Greek) but I

don't think in such a thorough-going or widespread way. I have used

them so much that they have become a method.

I suppose that I felt a thousand sneers at my shoulder. It was only

too easy to represent what I was doing as spoon-feeding. How is a

student going to learn vocabulary if it is always on tap? I very

carefully weighed these objections.

Once a pupil myself, I remember the stunning chore of looking

words up. I tried to learn vocabulary to cut down the work, but it

always remained tremendous labour, and after this essential

preliminary there was always the task of translating as well. I

suppose I looked up vocabulary in the old blue Macmillans and their

like. The entries were workmanlike but sometimes the translations

were antiquated or slightly askew, sometimes a curious rag-bag of

definitions that seemed nothing to do with the text in hand. The

smaller versions of Liddell and Scott seemed to take pleasure in

making it impossible to find difficult verb forms.

How had I ever acquired that special feel for the meaning of a

word that half-way decent Classicists start to have? Simply by vast

effort, wide reading and prose composition, I imagine. From the

mid 1960s I experimented both in Greek and Latin until from about

1975 hardly any 'O' Level or later GCSE set books were studied

without running vocabularies. The vocabularies, being from set-

books, were eventually learnt. Many sixth form texts were also

treated in this way. The key improvement was that students spent

more of their time puzzling out meanings, read more and faster,

used notes more selectively and sensibly. For a good many the

process gave them more interest, or was at least far less boring.

Using a running vocabulary, you feel a friend who has been there

before you is at your elbow.

It was very interesting to try this out on Homer, where vocabulary

is such a chore. The speed of translating was revolutionised, and

speed meant that one was meeting words more often, in itself an

aid to learning vocabulary.

There is a technique in preparing such vocabularies, and they can

be done well or badly. Some texts are of course not approached

until a certain stage, with consequences for the vocabulary. You

have to imagine what your students know or may need. They

mustn't be left in a half-way house where they partly use the

running vocabulary and partly look up.

These vocabularies are a terrific chore to prepare, and, close to,

seem rather trivial. Make a mistake and you feel a fool. Yet I am

convinced that they are very useful indeed.

Do I think vocabulary is unimportant? Not at all. Yet learning to

translate is more important and learning vocabulary can be partly

separated from this. If you use a running vocabulary, you can still

always look up the most interesting words in a dictionary, and

learn vocabulary from the lists.

For Latin texts the vocabularies were originally typed. This was

before word-processing and it was difficult to correct mistakes.

You were lucky to get a hundred copies. Greek ones were hand

written and run off on the old Banda machines, with hands

covered in blue ink. This meant that about sixty pupils could have

copies. Photocopying kept previous efforts alive; also the stencil

machine that burnt copies of the originals into skins for printing.

A number of colleagues joined in.

Sometime about 1980, I persuaded Robert Tatam to split the

Bacchae in two and we produced a complete running vocabulary

for it. Forty two sides of A4, double column! I then advertised this

in the JACT bulletin and it went out to many schools.

More than thirty five years later, many schools have discovered

the value of running vocabularies, and that the promise of using

them can make choosing Latin or Greek as an option a more

pleasing proposition for students.

Running vocabularies - the original defence

© MMXXIII T A Bird Classics

Classics resources

Running vocabularies - the original

defence

I want to argue that the use of running vocabularies is extremely helpful for those attempting to learn the ancient languages. For those unfamiliar with such aids, please look at my sample pages. I began giving out running vocabularies for Latin and Greek texts over thirty five years ago at Colchester Royal Grammar School. I was sometimes aware that others were trying this out (for instance, Reading Greek) but I don't think in such a thorough-going or widespread way. I have used them so much that they have become a method. I suppose that I felt a thousand sneers at my shoulder. It was only too easy to represent what I was doing as spoon-feeding. How is a student going to learn vocabulary if it is always on tap? I very carefully weighed these objections. Once a pupil myself, I remember the stunning chore of looking words up. I tried to learn vocabulary to cut down the work, but it always remained tremendous labour, and after this essential preliminary there was always the task of translating as well. I suppose I looked up vocabulary in the old blue Macmillans and their like. The entries were workmanlike but sometimes the translations were antiquated or slightly askew, sometimes a curious rag-bag of definitions that seemed nothing to do with the text in hand. The smaller versions of Liddell and Scott seemed to take pleasure in making it impossible to find difficult verb forms. How had I ever acquired that special feel for the meaning of a word that half-way decent Classicists start to have? Simply by vast effort, wide reading and prose composition, I imagine. From the mid 1960s I experimented both in Greek and Latin until from about 1975 hardly any 'O' Level or later GCSE set books were studied without running vocabularies. The vocabularies, being from set-books, were eventually learnt. Many sixth form texts were also treated in this way. The key improvement was that students spent more of their time puzzling out meanings, read more and faster, used notes more selectively and sensibly. For a good many the process gave them more interest, or was at least far less boring. Using a running vocabulary, you feel a friend who has been there before you is at your elbow. It was very interesting to try this out on Homer, where vocabulary is such a chore. The speed of translating was revolutionised, and speed meant that one was meeting words more often, in itself an aid to learning vocabulary. There is a technique in preparing such vocabularies, and they can be done well or badly. Some texts are of course not approached until a certain stage, with consequences for the vocabulary. You have to imagine what your students know or may need. They mustn't be left in a half-way house where they partly use the running vocabulary and partly look up. These vocabularies are a terrific chore to prepare, and, close to, seem rather trivial. Make a mistake and you feel a fool. Yet I am convinced that they are very useful indeed. Do I think vocabulary is unimportant? Not at all. Yet learning to translate is more important and learning vocabulary can be partly separated from this. If you use a running vocabulary, you can still always look up the most interesting words in a dictionary, and learn vocabulary from the lists. For Latin texts the vocabularies were originally typed. This was before word-processing and it was difficult to correct mistakes. You were lucky to get a hundred copies. Greek ones were hand written and run off on the old Banda machines, with hands covered in blue ink. This meant that about sixty pupils could have copies. Photocopying kept previous efforts alive; also the stencil machine that burnt copies of the originals into skins for printing. A number of colleagues joined in. Sometime about 1980, I persuaded Robert Tatam to split the Bacchae in two and we produced a complete running vocabulary for it. Forty two sides of A4, double column! I then advertised this in the JACT bulletin and it went out to many schools. Some thirty five years later, many schools have discovered the value of running vocabularies, and that the promise of using them can make choosing Latin or Greek as an option a more pleasing proposition for students.